Gary Steel | AUDIO CULTURE

This article was first published at Audio Culture in 2014 then updated following Victoria University’s reversal of support for Rattle in late 2015.

RATTLE RECORDS by Gary Steel

It could be argued that only a fool would start a record label with no commercial prospects or prerogatives, but that’s exactly what Keith Hill, Tim Gummer and Steve Garden did in 1991. Almost a quarter century later, kicking against conventional logic, Rattle is going strong, with a bulging catalogue that extends to 95 releases to the end of 2016. And counting. Not bad for a self-purported “art music label” that started out being run by three mates with loads of enthusiasm and specific skill sets, but little expertise in the ways and wiles of a record company. So, what did they do right, and how did Rattle become the de facto home of New Zealand music that didn’t fit the three-minute pop song format, and wasn’t alt-rock, but still belongs to this home we call the noisy land?

In 1991, session drummer and recording engineer Steve Garden, inspired by the decidedly non-conformist sound worlds of Phil Dadson’s From Scratch, and taking as a template the sparkling audiophile musical fusions of German label ECM, got together with buddies Hill and Gummer to act on an impulse.

“We could see that there was no label that gave a specific focus for this kind of music, art music; music that wasn’t driven by commercial imperatives, people who were composing within a framework that we felt wasn’t adequately represented by the labels that existed at the time,” says Garden. “The only option they had then was to go to Ode, but they were very broad in their reach, their focus wasn’t specific. And we felt that a label that had a specific art music focus, that looked at primarily acoustic instrumental music, including jazz and chamber… If there’s any way of describing what Rattle is, it’s a label dedicated to acoustic instrumental chamber music, but in a very broad sense.”

Hill’s real job was in film and television (editing, writing, filmmaking), while Gummer was a graphic designer.

“Rattle was a hobby label for the first 20 years,” says Garden. “We never made money from it. We occasionally paid ourselves for the work that we did, and for a while Tim received a small retainer to manage the day-to-day business. I was involved with the artists and recording, and Keith did an enormous amount of work in the background, all for nothing. We were very committed to the idea of Rattle, and the reason we could sustain it for all those years was because we didn’t allow it to become a business. And so long as it remained a label that was committed to an album a year, and something came along that we collectively felt we couldn’t not do, then we would do it.”

Te Ku Te Whe captured the public imagination, eventually reaching gold status and remaining Rattle’s most commercially successful release.

“Keith is extremely committed to culture. That’s why he got involved with Rattle – partly out of friendship with me and Tim, but primarily because he’s something of a visionary, and could see that Rattle had an important role to play in New Zealand culture. All three of us felt that, and that’s what drove us. We all had other ways to earn a living, so Rattle could just be what it was going to be.”

Although early releases by the likes of the Robert Fripp-inspired acoustic guitar ensemble Gitbox Rebellion and PVC pipe percussionists From Scratch quietly carved out a reputation for Rattle, it was Te Ku Te Whe (1994) that caused a seismic event in our cultural landscape. Musical anthropologists Hirini Melbourne and Richard Nunns reintroduced the sounds of te taonga pūoro – ancient Māori instruments – to a shocked and entranced nation. From museum exhibit to living, breathing, haunted evocations of a mysterious Aotearoa that predates Pākehā immigration, Te Ku Te Whe captured the public imagination, eventually reaching gold status and remaining Rattle’s most commercially successful release.

“It came about through a chance encounter I had with Richard and Hirini at Airforce Studio, where I was producing Midge Marsden’s Burning Rain. I went in early one morning and there was the two of them doing this amazing track for a documentary. I took a copy of it to Keith and Tim, and they thought it was fantastic. At the time we thought it would be an album that would probably appeal to musicologists and with a special interest in Māori culture,” says Garden. “We didn’t expect that it would be as popular as it was … and it still sells!”

Because the tradition had been broken, and there is no notation for Māori music, Melbourne and Nunns had to use their imaginations in regards to exactly how the music should sound, but they were aware that every instrument had a practical use in Māori culture. For instance, one of the instruments was originally placed on a child’s fontanelle at birth as an invocation. “There’s a really spiritual aspect to these instruments where they connect the player and the people he’s playing for with the ancestors. It’s like a portal, an invitation to the departed to come back and to have a presence within the lives of people today.”

Even so, while respecting tradition, Nunns has gone on to incorporate te taonga puoro into many different contexts, including dance mixes with Pitch Black’s Paddy Free and improvised jazz dates. (Sadly, Melbourne died in 2003). And earlier this year, improviser Rob Thorne released his own album of imaginative settings for te taonga pūoro, Whāia te Māramatanga. “He had an awakening, both in terms of his own relationship with his culture, but also these instruments, and where they can go, what he can do with them,” says Garden.

For many years managing only one or two releases each year, in 2006 things were suddenly ramped up, with four releases, one of which was what turned out to be a Herculean task, the John Psathas project (on CD and DVD), View From Olympus. “That was a massive undertaking, and probably only a label like Rattle could have done it,” says Garden. “Where money wasn’t an issue, it was about harnessing resources and harnessing talent, and applying for funding and begging and borrowing. And somehow, we managed to pull that one off.”

Winner of the Best Classical Album in the 2007 NZ Music Awards, View From Olympus was an ambitious work, and one critic said of it: “In classical music terms, this is The Lord Of The Rings.” The NZ/Greek composer harnessed the skills of a multitude of contributors, including US jazz player Joshua Redman, Portuguese percussionist Pedro Carneiro, pianist Michael Houston and the NZ Symphony Orchestra.

Rattle rolled on for around 20 years, with the advantage that Garden ran his own studio at the bottom of Anzac Ave, where he could record the label’s acts “basically for nothing”. “Because we owned it we could,” says Garden, “and it was a facility we could use for Rattle projects without worrying too much about how it was going to get paid for.”

When Garden set up his home studio in Sandringham, the show went on as usual. “With that kind of attitude we were able to keep Rattle going, and because we wanted the label to keep going it did. It didn’t need to pay a dividend, it didn’t need to make any money, it just needed to be as cost-neutral as possible.” While Steve’s activities were centred on recording, “Keith was always very good at finding people that he thought Rattle should work with – people like John Psathas, Gillian Whitehead and many others. He had an eye and an ear for what was happening at the time, and focused Rattle very well.”

By 2009 however, Tim Gummer was looking to concentrate more on his design work, so he stepped down as manager, while Keith and Steve worked hard to develop the label and increase its output. Garden had nurtured a relationship with Victoria University that began with View From Olympus. “It was hard work and we were under-resourced and the time pressure on the two of us was quite intense. We had bit off more than we could chew. Keith wanted to spend more time with his own writing and filmmaking, and he wanted to see Rattle become much more of my focus,” says Garden. “I wasn’t so sure about that to begin with. The commitment frightened me to some degree. But in the end I could see it was the most sensible way to go, and Keith left me to it.”

The relationship between Victoria University and Rattle began with Rhythm Spike (John Psathas, 1998), and developed further with View From Olympus (Psathas, 2005), but it was the slew of releases in 2011 that really brought the label and university together. “It just so happened that 2011 marked the close of a five-to-six year research cycle, so there were a lot of people within the university completing projects, including recordings, and the requirement was that these had to be published. Rattle took many of these projects on, in part because they came with budgets that covered release costs. As a result of the work we did that year publishing VUW research outputs, the university proposed that they become more actively involved in the label. They saw the value of Rattle as a cultural entity, but also in terms of what it would bring to them, so they were keen to ensure that Rattle survived. Eventually they just said ‘why don’t we buy the company and you work for us?’ For me, VUW’s offer meant that Rattle’s future would be secure, and that the label would be able to access skillsets it had long needed, so I happily and optimistically agreed.”

In April 2013, Rattle became part of Victoria University Publishing under manager Fergus Barrowman. “Fergus is much more business minded than I will ever be, which is what Rattle needs,” Garden said at the time. “I’ve managed to keep Rattle solvent to now, but Tim, Keith and I were never business people. We don’t think that way, and didn’t set Rattle up as a business as such. The label has always needed someone to give it the structure necessary to develop, someone with a head for marketing who can liaise with media and seek out third-party licensing partnerships. Part of the reason Rattle has always remained fairly small is that we have been limited in terms of what we can effectively do to take our music out into the world. Becoming part of Victoria University offers real possibilities in that respect.”

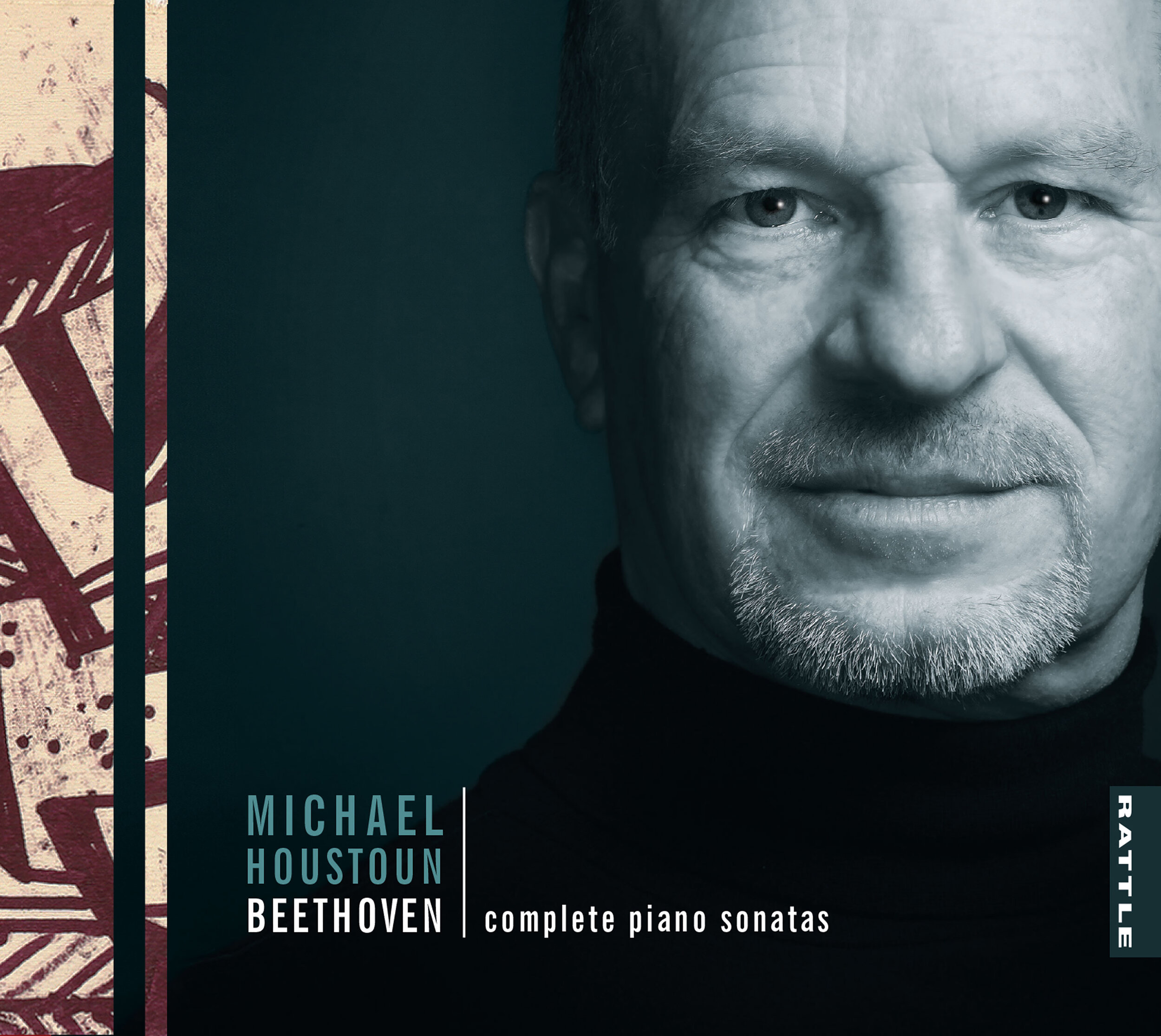

Under VUW’s stewardship, Rattle embarked on a number of projects, inculding a genuinely mammoth one, easily its largest undertaking to date: Michael Houston’s recording of Beethoven’s 32 piano sonatas. The 14-disc boxset was recorded on the splendiferous Steinway in Victoria University’s Adam Concert Room over three sessions in April, September, and December 2013.

Ludwig van Beethoven may seem a strange choice of material for a local label, but Houston is most assuredly one of our most treasured classical performers. And anyway, labels as diverse as Lil’ Chief and Flying Nun have occasionally released albums by foreign artists. One thing is for sure, like other Rattle releases, the Beethoven box will look like a million bucks. Even their single CD sets come in lavish, hardbound cardboard cases that look more like books than jewel-boxes, and Garden is staunch on that point. “The presentation of the music is almost as important as the music. When you pick up that CD, it tells you something about the attitude behind the making of this piece of work before you even hear it. So if you’ve got something that’s presented in an impressive way, immediately people are on your side. They want to hear this.”

But Rattle releases are also available in CD quality digital files from their website, and Garden is playing around with the idea of releasing real hi-res files on USB sticks (but still with gorgeous hardbound covers) for audio nuts with great home stereos. Unlike that other great local label, Atoll, Rattle’s classical music focus is less on standard repertoire and more on new music, what composers are doing now, as well as historically important avant-garde NZ composers like Douglas Lilburn.

“Michael Houston doing Beethoven is a no-brainer for us: of course we’ll do that, because it’s Michael Houston,” says Garden. “And it’s Beethoven, some of the best music ever composed. So we’re not staunchly just new music, but our general focus would be contemporary and forward thinking music. That’s Rattle’s general vibe, but we don’t limit ourselves to that. We see ourselves as a New Zealand art music label, and that’s a broad umbrella. So if something takes our fancy and we think that it falls within our ethos, then we’ll go for it.”

In May 2015, a little over two years after becoming part of VUW, senior management called for a “review” of the label. Five months later, on October 20, Fergus informed Steve that VUW was no longer interested in owning Rattle. Divestment was completed by December 20, by which time Garden had negotiated the return of ownership of both the label and studio. It left him and the label broke, along with a responsibility to release projects currently in train.

Consequently, 2016 was a tough year for Rattle, but the label survived, in part due to the support and encouragement of Creative NZ, Roger Marbeck, private patrons and Rattle artists. “The university’s decision was a huge disappointment in terms of losing the promise a solid and secure future for Rattle,” says Garden, “but it was evident by late 2014 that the university had expectations of the label that simply weren’t viable. I’ll never really know what motivated them to buy Rattle, or what motivated them to drop us. What I can say is that I’m relieved that Rattle wasn’t destroyed in the process. It very nearly was.”

Some of Rattle’s releases have been demanding and experimental, and quite beyond genre categorisation. A great example that Garden cites is a 2012 release by Adam Page and James Brown – two guitarists from Adelaide – and John Psathas, who contributed on a production level and compositionally, but didn’t actually play on the recording. The Harvest, released on sub-label Rattle Jazz, “is really pushing what jazz could be. There will be many who just wouldn’t see that as a jazz album at all.”

Rattle certainly has its edgier releases, but Dark Light, the 2014 release by pianist Jonathan Crayford, recorded with a bunch of New York heavy hitters, finds a poignant balance between innovation and tradition, invitation and seduction, and is as startling musically as it is easy on the ear.